On the Easel Blog

WHAT’S THE STORY?

As a figurative artist, I am mostly concerned with painting and drawing facsimiles of human beings in various poses and attitudes. Though I am well aware these are only illusions, in order for them to be successful, i.e. believable, they must look like actual people, not cartoon characters. I have noted in previous writings that there is quite a bit of leeway in this descriptive mode– I am known for my blue noses and green mouths. Basically if the form is captured adequately, we accept that this is a painting of a living being. This is remarkable in and of itself. We seem to be ok with the lack of specificity. Is it that we are so willing to suspend our disbelief, or simply don’t care for accuracy. We say…close enough.

We assert that it is necessary to get this believability down, but, we ask, is it sufficient? I think not. In order to be satisfied I have made something worthy, it needs to incorporate something else. What exactly? My answer: a story. Why should we care about this imaginary being, that’s the question. It may look good, but so what?

I recently did this painting of a woman with wild hair (secret: I love painting wild hair with my wild hair brush– don’t tell anyone). Anyhow, she also had these wild eyes and a shocked expression. Whether this was due to ineptitude or just an accident, I cannot say. What I can tell you is that I realized I had to give you a reason for this character to sport this hairdo and also account for her shocked expression.

So what did I do? I made a square of white on her lap to suggest a piece of paper, scribbled some squiggles on the paper, and titled the painting ‘THE LETTER’. By doing so, I gave you the reason for her expression and challenged the viewer to wonder what was in the letter. This act elevated a painting of a woman with wild hair to a narrative piece of work.

Did I make the painting better? Not necessarily. I just gave you something to wonder about, to think about, and by doing so, possibly made it relevant to you. I gave it meaning, and that is what we hope to accomplish in art– not just to make pretty pictures, but to tell stories about the human experience.

Here is THE LETTER:

WHEN IS ENOUGH ENOUGH?

It’s awfully confusing, this decision we make in art of when to go simple and when to go full throat. It’s a conflict to be sure. On the one hand, we love detail– color, pattern, the gorgeousness of the paint…so tempting. Yes, we love it. On the other, the desire to clear away all the detritus, all the unnessary little notes, and just reveal…so truly satisfying. We flip flop from one to the other, canvas to canvas. Can we ever find a balance, decide?

Here’s one for simplicity. I was working on a portrait of a woman in which I wanted to do the former, go for broke, and paint just this absolutely wild hair all over the canvas. That was my intention.

But in the process of sculpting her in paint, she developed this absolutely piercing and penetrating stare. What in the world is she looking at, you cannot help but wonder. I love it whenever a painting suggests a narrative, and I seemed to have one here. But what of the wild hair, you ask?

Well, I realize that the wild hair will just obfuscate that stare, take away from it and distract the viewer. I didn’t intend it but the painting is about that stare, and only that stare. To decorate, embellish, beautify, do anything really, would only diminish the painting’s new intention.

So she stands, clothed in black, no details, just that face, those eyes, looking at something she can’t help seeing. Just to satisfy my other longings, I add a few clouds and a black bow. I am done.

Here she is: I SEE YOU.

By the way, stay tuned. You know I have to do the wild hair painting too. Another day, for sure.

INNER OUT

You may have heard artists describe their work as “personal”. I have used this term myself in pinpointing certain works that are closer to my heart or that I prefer over others. But how does an artist make a work personal? How exactly does that happen?

You have heard me explain many times before that making art is a process, that the artist may start with an intention, but the final destination is unknown until the last mark is made. This suggests that our intentions are only part of the story because they erupt from our conscious mind before the unconscious has had its way with the artist or her canvas.

It is that unconscious mind asserting itself that contributes to making the image personal. Here’s an example of how this has recently come to life in my studio.

I started with a photograph I found of a woman walking towards the light. Like most painters, light is a crucial element and is foundational to our inspiration. I liked the photograph because it gave me an opportunity to play with elaborating the quality of the light and how it fell on the figure.

Since I am not interested in copying the photograph, just using it as a starting point, I first flipped the image so the figure was seen walking left instead of right. In the photo she was wearing an old fashioned dress with a bustle. I wanted my female figure to be modern so I cut the dress and bared her leggings. I altered the drawing so she appeared not just to walk but to march towards the light. I turned the left side of the canvas into a suggestion of a door. Now she was marching to the door.

Because I wanted to identify the source of the light on her face, I drew a rectangle in the door to suggest a window. I also added a floor and then some leafy patterning on the floor. I liked the patterning so much that I repeated it on the wall. But, for visual logic sake, I had to also identify the source of the pattern? It had to come from the window.

Yes! I was struck with painting lightning! It occurred to me to add a head of a man in the window. His face was surrounded by the pattern. Now it made sense. The woman was marching for a reason– to answer the door. He was bringing something positive into her life represented by the pattern. In that moment, I knew the name of the painting: “The Visit”.

I realized that I had created an image representing a deep wish. I had recently come to the decision that after years of living alone, I wanted a partner. My inner self had entered the studio to project my deepest feelings on the canvas. I did not intend this, but it happened anyway. This is the way we make our work personal, by just following that proverbial “yellow brick road” that leads to the wizard, to oz, to ourselves.

Here is “The Visit”:

WHY MIXED MEDIA?

Why doesn’t a single media suffice?

It can, of course, there are marvelous art works in a single medium. But every medium contributes a vocabulary, a range of effects that are permitted, suggested and realizable with that substance. Each provides a set of textural abilities that when provided in concert produce, what? Something new, something unexpected.

I am a figurative artist. Though I have many times attempted to create purely abstract works, I mostly fail. Without the figure, I am lost. Regardless of how interesting or attractive these abstractions are, they do not support a full work.

So, failing thus, and of course experiencing diappointment, I find myself cutting up, tearing my failed attempts– deconstructing them. And then what? They go in my box of goodies to be reconstituted another day.

Sometimes, on a day when there is nothing new on the easel, I take a failed attempt at a figurative piece, go into my box of disembodied abstract fragments and start matching and filling in and glueing them willy nilly onto the portrait. This feels like a very liberating exercise. If I am on that day, before long the not great figurative painting begins to wake up, to become something actually interesting and worthy.

This happened with this work I call “Very Red” where I used a bunch of snippets from a very disappointing foray into alcohol inks, and applied the cutouts to a pretty disappointing portrait of a woman. Wowie zowie, one failed piece made the other failed piece just fabulous. Here she is:

The addition of the abstract elements make it so much more interesting to look at. I love the incongruities, the way the abstract fields demolish the conformity and regularity of the head. They do for the piece what I could not do when I was painting it– free me from my own conceptions. Using multiple media is a tool to open the artist’s expressive possibilities. If you haven’t already, try using a few to open yours.

VISUAL MEMOIR

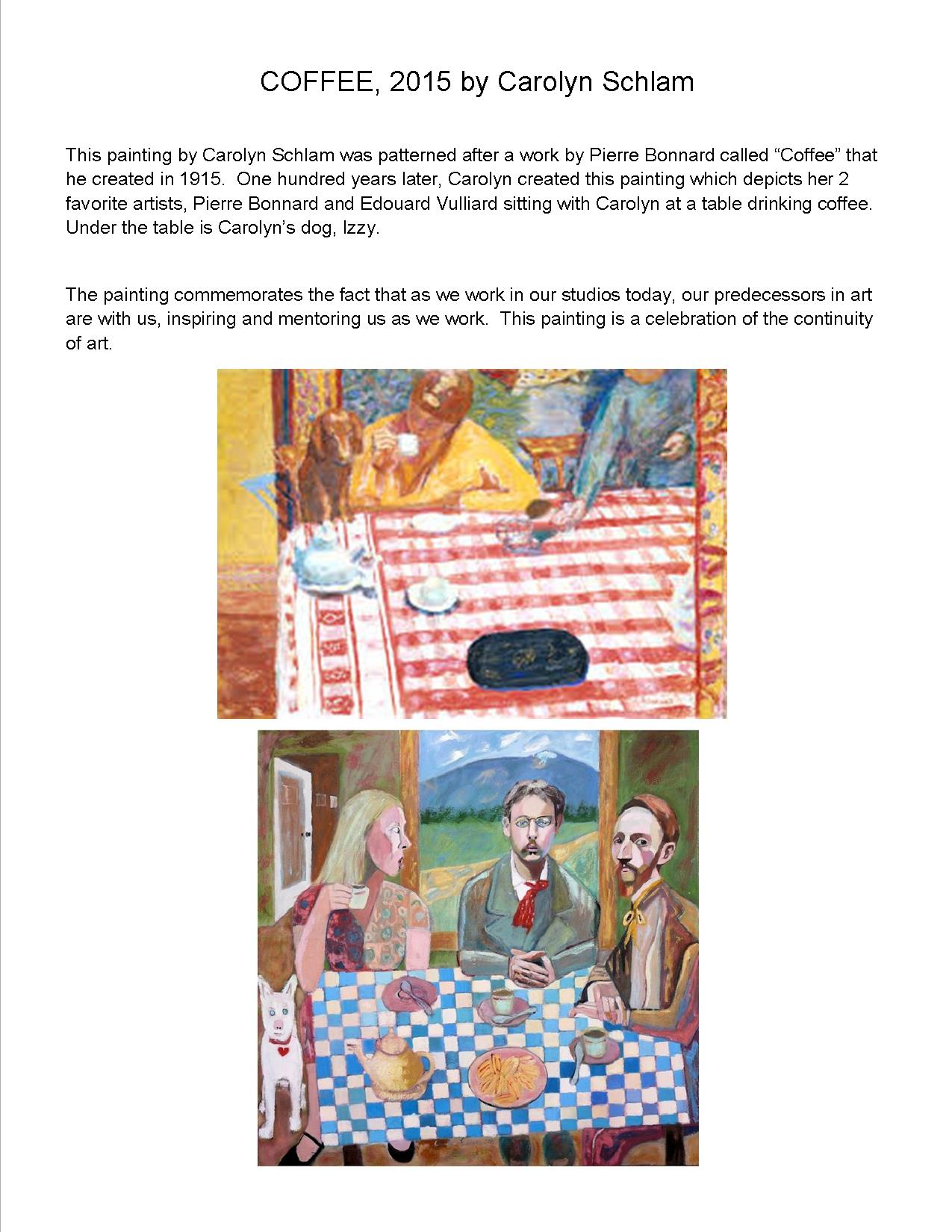

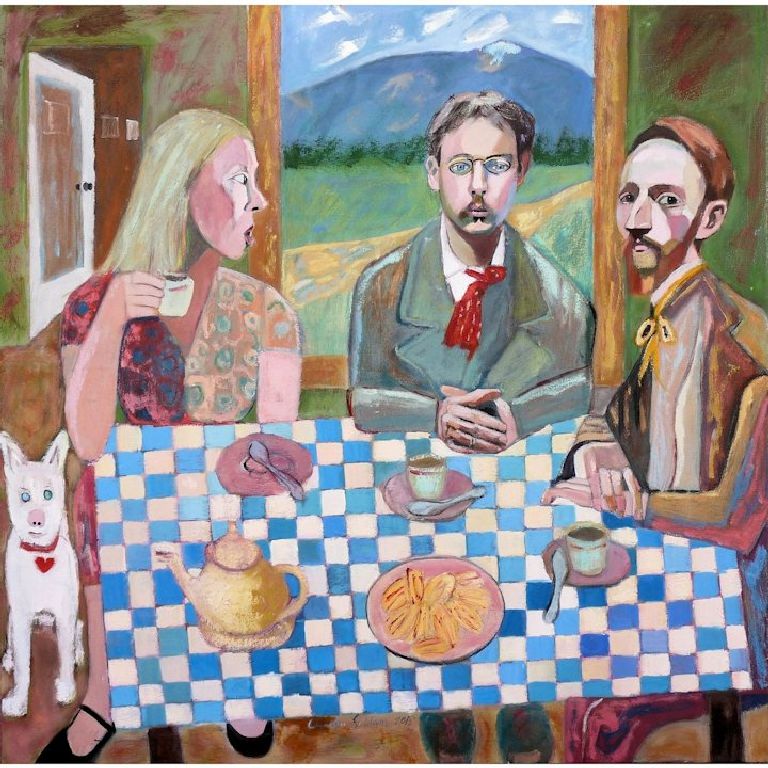

Today I was notified that a favorite painting of mine called “Coffee” had been accepted into a literary magazine. This pleased me very much and I decided to write a little about it for this blog so here goes.

The story is this: It was 2015 and I was living in Taos, New Mexico. I decided to make a self portrait and I was searching for a theme. Two of my very favorite artists are the marvelous Nabi painters Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. I adore them for their beautifully patterned interiors and tapestry effects which I have tried over the years to emulate in my own way.

So to honor them, and my own identity as an artist, I decided to include them in a self portrait. I went looking for paintings by both of these artists and stumbled upon one by Bonnard called “Coffee.” I was excited to learn it was dated 1915, exactly one hundred years back. Aha! Destiny. This had to be my source.

I studied the painting. It had a red checked tablecloth. It featured a dog, a pot, a plate, and a figure holding a cup. The title was “Coffee”. Mine would have the same features. I would paint myself sitting at the table with Bonnard and Vuillard and we would drink coffee. My dog would be by my side. I’d go with a blue and white checkerboard for novelty and supply some madeline cookies on my plate.

I found photos of the two artists. For myself, I decided I would try to capture a look of startled amazement as I looked over while sipping my coffee, only to discover my two compatriots had materialized, stepping out of history to join me in my Taos studio.

It wasn’t an easy painting to make, that’s for sure, but I think it’s pretty good. I call it “visual memoir”

but it is memoir of an experience I created, a visual dream perhaps, something that did not actually happen but seems to be now, apocryphal, something I wished into being.

That’s the magic of art, I think.

See it here: Bonnard’s painting and mine.

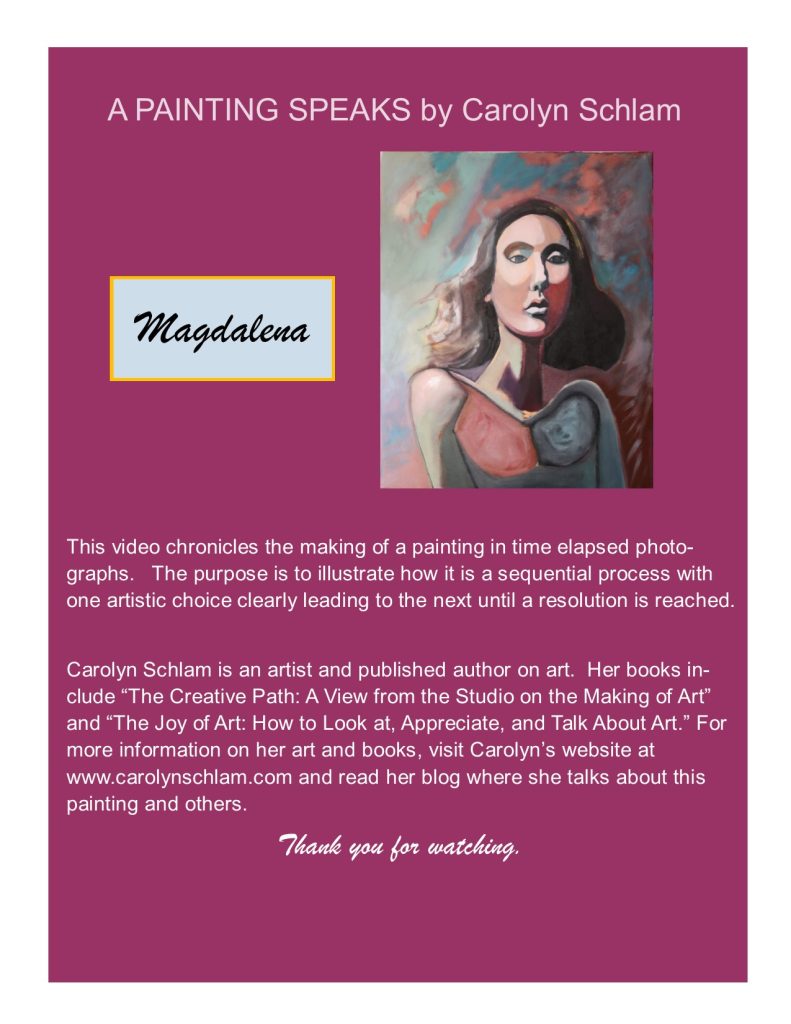

A PAINTING SPEAKS: MAGDALENA

When you look at a painting on the wall of a museum, it is a fait accompli, one and done. You have no idea how the artist arrived at this destination, and, as much as you enjoy the finished product, there’s something missing. You caught the ending but didn’t get the whole story.

The artist, working alone, is the only witness.

So, I tried to rectify this missing tale, in at least this one example. I set up a camera on a tripod fixed on the canvas on my easel, and I painted this oil portrait, stopping every now and then to snap a photo of what was on the canvas at that moment. It took about 5 hours to complete the painting over the course of about three days. I then put the photos in sequential order and had this little video made showing a time elapsed story of the series of artistic choices that became this painting.

The thing is that when you are working, it is a process of forward and back, adding and subtracting, in an attempt to correct, amend, change, perfect, express, clarify, order and improve one step after another. Notice that it is impossible to complete one area of the canvas and then go to another. The eye makes the artist leap from pillar to post. Add some yellow, and the canvas cries out for blue. Make a line and then no, it has to go. Change, change, change…it’s a frantic show.

Nothing is good enough- you could keep adding forever and never finish. There’s a famous writing by Proust, I think, who writes about an author rewriting the first sentence over and over again, never getting it perfectly right. He cannot progress past page 1. And that is such an important lesson, maybe the most important, for a creative person to know. It can never be perfect, and you can write and rewrite and paint and repaint endlessly, and never arrive.

To arrive you must move, you must travel. Movement is life, said my dance therapist, Blanche Evan, and she was still 100% correct. Art is movement too.

As you move and change, certain things get decided and this limits where you can go, at least for this particular journey. Eventually, as you keep working, you get to the end of the road where there are no more choices, the road is blocked, and it’s time to close up shop and go home. The painting is as done as it can be.

Remember, whether you are happy or disappointed, tomorrow is another day and you will start out on a different road, hopefully, make different choices, and wind up somewhere else. Let it be and go again.

I hope you get the idea of a typical painting journey watching this video. Please get in touch if you have questions by writing to me through the contact form. I’ll get right back to you.

Thanks for watching.

THE ARTIST’S SIGNATURE

You’ve probably heard folks comment that people look like their dogs or that their dogs look like them, haven’t you? Or similarly, that husband and wife look remarkably similar, are like twins in male and female versions. It’s a conundrum to be sure, but these propositions also have a corollary in the world of art: that an artist always paints him or herself. Could this be true, and if so, why?

I think it is true and it really is not preposterous in the least. We are most familiar with ourselves, and have gazed upon our visage in countless mirrors, store windows and other reflective surfaces. We have also spent much time gazing upon our relatives, whose forms and proportions are genetically linked to our own. These images have stuck and formed a library in our minds, our own set of google images, if you will. We unconsciously turn to it when we set to work in the studio.

If we are figurative artists and paint faces and figures, it may be very apparent that we veer towards a certain characterization, and less obvious if we are painting pots or trees or abstract designs. But even if your subject is the latter, it still follows a familiar rhythm and pattern that we recognize as our own. That squat pot shape you favor may bear a connection to your Dad’s belly or your own, and the decorative strokes you find yourself returning to may call to mind the wallpaper of your childhood home.

I can clearly testify to the latter as I am quite guilty of using and overusing the checkerboard pattern in many paintings, clearly an unmitigated copy of the black and white linoleum on the floor of the apartment my family lived in for some 52 years. “Nostalgia”, thy voice is checkerboard. (see sample below).

Face it: There is no escaping your DNA and that includes your artistic DNA. It is yours and it belongs to you. Quite simply, it is your “style” or your “signature”. Along the way, you may begin to see the same shapes, colors, effects showing up again and again on the easel, and it’s a good thing when you begin to recognize it and work with it. Making your work personal and intentionally expressive of who you are, what you’ve experienced and what is important to you, is the north star, leading you to become the artist you were meant to be.

I have worked from many models and photographs in crafting figurative works of art. People will see the finished work and say “that looks like you” or “that looks like your sister” but neither I nor my sister were on the model stand. It really doesn’t matter at all who the model happened to be because, though you may think so, the model is not the true subject. The true subject is yourself and the purpose of your art is to find and understand and express your absolutely unique essence.

So all the faces and all the pots and all the squiggles are all you. That’s why they look like you after all.

Here is that painting called “The Sisters” with one of my checkerboard floors and a portrait that looks like me called “The Schoolgirl” I did decades ago.

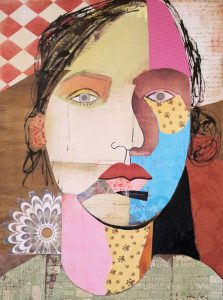

CUT AND PASTE

There’s a lot of mathematics that goes into making a picture. It often just seems like a process of addition and subtraction. There is a nothing, a void, and then poof, you add a spot of red or a line or two, and you are off to the races. As notes accumulate on the canvas, invariably something seems wrong or out of place and it simply has to go– a subtraction. It’s then on again, off again, until that magic moment when traffic stops and you are done.

A medium that is a perfect expression of this process is collage, and I adore it for its versatility and simplicity. Years ago a student of mine asked if I would like a collection of decorative papers a friend of hers had collected and never used. Yes, please.

That trove of papers was one of the best gifts I have ever received. A while after the gift I found an old chest someone had discarded on the street and I brought it home. I painted each of the seven drawers a color in the spectrum and then divided up my papers in the corresponding drawers. This way I did not have to hunt through the gigantic pile to find a green or a red. What a find. A veritable gold mine.

My process is to paint or draw something on a large white paper, and then to cut and paste fragments of my papers onto the paper. The great thing is that I can move the pieces and readjust them to my heart’s content before making a commitment and glueing them down. This is such a fun and engaging activity—I have whiled away many an afternoon making one of these puzzles.

They do feel like puzzles, fragments that fit together, and when I complete one I feel like I have solved something, the question of the day. I recommend this medium to many wishing to explore art making as it is so forgiving and so fun.

Here’s a latest collage of mine called “Dare to Be”

REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST

Memories of a time in my life when days of making art felt like the greatest luxury in the world have returned. I was just out of art school and in my very first art studio in Greenwich Village. It was a giant loft I shared with many other women called The Womens Workspace. The place had been rented by a women’s liberation organization called “Radical Feminists” and was a women only space, no men allowed ever, even to visit. I rented my little bit of space in the back near one of the 27 windows– we had the whole 9th floor, 2500 square feet in total—because it was only $15 a month. Our total rent was only $150.

In spite of the teeny rent, the steam heaters went at full blast, and though we had no amenities whatsoever, not even hot water, it was toasty warm always. This was my ritual: I would walk there in the morning, stopping at the deli on the corner which offered delicious homemade soups. I would select one of the soups, a buttered bagel and a coffee and then happily hightail it up to the studio to spend the day and paint.

And stand and paint I did, all day, except for rest stops to sit down for a moment, and savor my goodies, and gaze at my canvas. In the warmth of that space, in the quiet, with gray skies outside, I slid into a reverie of creative absorption, deep into a place that was all my own, no distraction, no worry, no care, other than finding the right red and the expressive line, and the very purpose for my existence on earth. To paint, to make an image that was new to the world, that was never before and never would be again, encased in the warmth of the day with the need to express making everything else irrelevant.

To have experienced such passion and boundless joy has been the gift of my life, and I remember this time as the purest and most compelling of times. It comes to me still, sometimes, when I am at the easel and find myself flying, but not as potently as this time, when it was all so new and I was discovering my possibilities in such an unconscious way. It’s difficult to keep passion alive, I remind myself, in this, just like any relationship. We get jaded, sidetracked, spoiled.

But today in the studio, working on something new, when it was cold outside, and the house was warm and the canvas was revealing secrets, I was back there on the 9th floor, in my cocoon of art. The passion was still alive and I remembered.

Thank you universe for a wonderful life and another joyous day.

Here’s a painting of a nude I made in that loft, 40 years ago, from a model.

THE QUALITY OF ALIVENESS

I am a painter. I use oil paint on canvas to create my portraits. I retrieved this portrait “The Red Hat” from my warehouse yesterday to rephotograph it and I got a chance to look at it again.

What impressed me was a quality of aliveness that this portrait gives off and I thought I’d make a closer examination of what makes that possible.

Of course, as I am drawing and applying paint on the surface, I am trying to create something that is vivid, that represents the way the light falls on the hills and valleys of the face, that is believable as a woman’s face, that is pleasant to look at. I don’t want the color to be local or imitative, but I don’t want it either to be garish or false. I want the hands to look like hands, not claws, and the skin to feel like skin, not leather or metal.

So there is imitation involved, I cannot deny. I am going for a certain verisimilitude.

Yet, if she is successful, one of these women I am painting, she must feel alive. Of course, she is not; she is just paint. But this is the trick and the reward. To make something that appears to live and breathe. This is impossible, you might say, and you are certainly right.

But look at her. She is not perfect by any means. Some of the paint could have been better applied. And yet. She seems alive. How did this happen? How did I accomplish this?

There is no formula, and the task does seem impossible. But here is the evidence. It can only be one reason and one reason only. My own aliveness has been injected into the image I have created.

Like a soul flying out the window and landing in a new person, she has been breathed into manifestation.

Look for this as you look at art and you will find it everywhere. The magic of creation.

DEVELOPMENT OF AN IDEA: THE PAINTING CALLED “FEMINA”

As they gaze upon a new painting, viewers may wonder what possibly has inspired the work. How did the artist come up with this particular visual idea, and why? Was it something the artist witnessed or was it derived from a source like a photograph? Perhaps it was just imagined out of the blue, in a dream perhaps, a chance meeting, a passing glance that stuck. However did it pop into consciousness and onto the canvas this particular day?

Usually for me, it is something visual that has zinged me. The light on an object, a pair of colors that resonate, a position or pose of a figure that evokes empathy… For this work, called “Femina”, however, the genesis was an idea I decided to try and express visually. I wanted to depict the cliché concept of the feminine identity. Not the spiritual or emotional idea of femininity, but instead, the conventional, societal construct.

What were the elements I needed to include? I decided on the ingredients: blond hair, blue eyes, a bewildered expression, a dress, preferably printed, a bow in the hair, and most essentially, the purse or pocketbook, carried in a particularly haughty manner. The latter proved to be most essential and difficult to achieve. With no model to work from, I went to my own closet, got a handbag, and put it over the crook of my elbow with that particular hand gesture I wanted to imitate, and painted it in with the other hand. It proved to be exactly what I needed to deliver my message visually.

After several experiments on the background, I decided on black to set my female in stark relief, but the painting cried out for more. I found the answer in a home depot store in the form of a wall stencil. Somehow setting the figure off in front of what appeared to be a wall or enclosure was just the thing to make the point that the societal concept of femininity that we are so attached to and persists in the consciousness of both women and men is so detrimental and can be imprisoning.

So the work was now complete. Here is “Femina”. The value of art is that in an instant, without language, the idea is apparent in a way that no other medium could communicate. The image is an exaggeration, of course, but it is also eerily familiar. We recognize what she represents. She looks at us and asks for our opinion of her. She questions us and we cannot look away.

“FEMINA” by Carolyn Schlam, Oil on canvas 40 x 30”, 2022